The Volta Laboratory’s Legacy

The Volta Laboratory’s commercial successes—a way to engrave sound on a wax cylinder and a new machine to record cylinders and play them back called the graphophone—transformed Thomas Edison’s “talking machine” novelty into a workable technology. These successes spurred others—including Edison, who resumed his phonograph work—to enter the emerging industry of sound recording and playback.

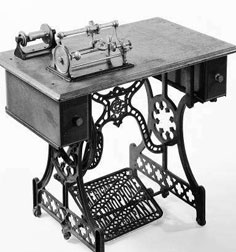

Charles Sumner Tainter, one of the original Volta Laboratory Associates, continued to improve the original concepts for the graphophone after 1885 and stayed with the project to see the first machines into production in 1887.

The graphophone became a widely used dictation machine for business, eventually made and sold by the Dictaphone Corporation. As recorded-sound technologies branched into public and home entertainment, another part of the Volta Laboratory’s business evolved indirectly into Columbia Records.

Tule Indians of Panama recording songs on a Dictaphone at the Smithsonian, 1924. Portable versions of machines for making cylinder recordings transformed the study of cultures in anthropology and folklore. (Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

Constructed in a Bridgeport, Connecticut, factory that made sewing machines, the first graphophones were table-mounted and treadle-operated. The experimental machines had all been hand-cranked, and maintaining a uniform speed of cylinder rotation presented a major engineering problem.