Wave Machines

Historical Context

Wave machines and wave models began to appear in science classrooms around the middle of the 19th century. They were used to teach the principles of waves, which were central to a new understanding of the physical world that we now refer to as “classical physics.” Classical physics was a synthesis of many subjects – acoustics, heat, light and, later, electricity and even magnetism – all of which could be explained in terms of different kinds of waves. Teaching the principles of waves thus became one of the basic goals of the science classroom. And since most waves are too rapid to see directly, a variety of wave models and machines were developed to depict them. Compared to other kinds of waves, sound waves are relatively simple and can used to demonstrate nearly all the properties of waves. They can also be represented as being either longitudinal (like a pressure wave) or transverse (like the up and down waves on a vibrating string). Because of this, acoustics was commonly the first topic that students studied, and a wide range of demonstration models were developed to assist them. Wave machines were widely used until the early 20th century, when a series of important discoveries were made that could not be explained by wave phenomena alone. Although waves continued to be important in many fields, light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation were now explained in terms of sub-atomic particles and wave packets. The age of classic physics was over and wave machines began to slowly disappear from the science classroom.

Supporting Artifacts

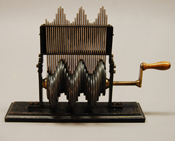

Snell’s Illustration of Sound Waves

Ebenezer Snell was the professor of physics at Amherst College and a central figure in science education in 19th century America. In the 1850s he developed a series of wave models that he used in his teaching. The models were very popular and by 1860 five of them were being produced commercially for use in schools and academies.

In 1877 the Boston firm of E.S. Ritchie & Sons, which made Snell’s models, published a catalog with this description: “Snell’s Illustration of Sound-Waves, or waves of condensation and rarefaction. In this species of waves the particles simply oscillate back and forth in the line of the wave. Thirty white balls are arranged to form two and a half waves: each ball oscillates one and a half inches. A black screen is placed behind the balls; the frame, of mahogany, is thirty inches in length. The instrument illustrates longitudinal vibrations in a most striking and beautiful manner. …..$35.”

Transverse Wave Machine

This instrument was manufactured in Germany around the turn of the 20th century. It is surprisingly small and can easily be held in one hand. It was designed to be placed in front of the lens of a projector and to be used for “shadow projection”, which was a teaching method more common in Germany than in America. This machine only shows the sinuous motion of a transverse wave, but a more elaborate version was also made that included a series of angled rods that allowed it to also demonstrate longitudinal waves.

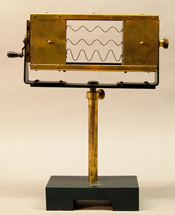

Projection Wave Model

This apparatus consists of three wires, each bent to resemble transverse waves. The wires are mounted in a rectangular brass box that was placed in front of the lens of a projector. The top two wires are identical, but positioned so that their shadows appear to move in opposite directions as a crank on the side of the box is turned. As they do this, the crests and troughs of the waves alternately lineup and overlap. The corresponding “interference” of the two waves is seen in the changing shape of the third wire. The sliding covers on the box allowed the instructor to keep the demonstration hidden until the rest of the presentation had been completed. Although it is unmarked, this apparatus bears a strong resemblance to wave models made in the early 20th century by the William Gaertner Company of Chicago.

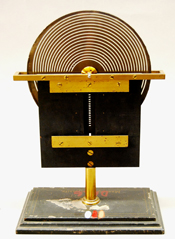

Crova’s Disk

André Prosper Crova was a faculty member at the University of Montpelier. He invented this acoustic wave model in the 1860s and commissioned the prominent Parisian acoustic instrument maker Rudolph Koenig to manufacture it for him. It was first shown at the 1867 Paris World Fair.

Crova’s apparatus consisted of glass disks which were first painted black and then had a series of precise curves traced through the paint to the glass. The disks could be viewed in different ways, but generally were projected through a slit as they were rotated. The short arcs of the circles projected in this way represented particles of air and as the disk rotated these “particles” moved in precisely the same way that air moved when set in motion by a sound wave.

Crova’s disk was widely used and was manufactured well into the 20th century. His original apparatus included eight separate disks that could show “propagation of a wave pulse, reflection of a wave pulse, propagation of a sound wave, reflection of continuous vibratory movement, fundamental tone of sound pipes, first harmonic of sound pipes, vibrations of ether and interference of two vibratory movements.” Over time, a variety of additional disks were designed which extended its range even further. In 1889 a complete set of eight disks together with a viewing stand cost $80.